The first "blip" for an inclusive mentoring manager is the first time a new mentee/hire does not meet expectations. Many first-time managers ignore this early warning sign, and sacrifice their own productivity and well-being in the process. Here's what to do about it.

So you've brought on a new person. Congratulations! But has the first blip happened yet?

So you've brought on a new person. Congratulations! But has the first blip happened yet?

The first blip is the first time that your excellent new mentee/hire does not meet your expectations. No matter how fantastic your person is, there is going to be some sort of blip. You'll notice it on your radar usually within the first 30 days that a person is in your lab. Second, not only is it important to address a blip - it's key that you avoid one of the most common new mentor/manager mistakes: minimizing and under-responding to your new performance or conduct data point.

What does a first "blip" look like?

For the person you are mentoring/supervising, the blip may be a competency growth area that you already had assessed from your interview or your mentee self identified as a learning curve, like their lack of familiarity with a technique or lack of confidence when communicating. It could also be something entirely unexpected, where you do not yet understand the ramifications - such as they overestimated their knowledge or abilities in a particular area, or have core "work hygiene" issue (such as showing up to meetings on time, being reliable, etc.)

Whatever it is, the real issue is how you respond to this blip. Many first time managing mentors (or mentoring managers!) under-respond or minimize this data point. What does that look like?.

AskaManager.com has an excellent benchmark for feedback: Not "Does it bother me now?" but "If this person is still doing this in a month, will it bother me?" If the answer is yes, that's a sign you need to address it.

- Not addressing the issue with the person at all

- Minimizing the issue by saying "it's okay" or "it's not a big deal" (when it would be a big deal if it happened repeatedly).

- Halfway discussing the issue - for example, raising the issue but not clarifying the impact of their action/lack of action (or discussing that you want different behavior but not explaining why that different behavior is important.)

- Taking on the additional work to "cover for them" (you take on additional work - including such things as completing the task for them or moving around your schedule - without ever making them aware of the fact. Therefore the person never realizes the true cost of their performance or behavioral issue, and you become resentful by the additional work and what you may judge as their cavalier attitude.

Why do managers (and managing mentors) minimize or under-respond to this first data point?

If your position is defined as a mentor, or have a strong mentoring identity even if you are defined as a supervisor, you might hesitate to address the issue or say anything at all the first time a blip appears - such as your person missing a deadline. Why?

- You might incorrectly assess that whatever is happening is a "one-off," or happening because they are new. You might assume that time will resolve the issue, and don't realize that part of that experience that will fix the issue is making it clear that the situation isn't meeting expectations.

- The mistake or behavior does not significantly negatively impact them at this time, so you let it go rather than commenting on it.

- You more heavily weigh your concern of not demoralizing the person with corrective feedback, than you supervisory/mentoring role, which is to set and clarify expectations. You might also closely identify with the person, and incorrectly imagine that the person will respond as they believe they would. For example, the person shows up late, and you might think: This person must know that this a problem - I mean I know this is a problem. If this happened to me, I would get up 30 minutes earlier next time. I'm sure that's how the person will handle it. No need to embarrass them by commenting on this.

- You won't want to be perceived as being "nit-picky" or a "micro-manager." You may also be a little conflict avoidant.

- You may feel that too much time has lapsed to address the issue, and are not sure how to address it after the

The result is that many first time and experienced managing mentors will experience a strong urge to not address the situation. The problem with that response is that the person will not realize that what they've done is a problem for you. Secondly, even though you didn't discuss it with the person, you might have already consciously or unconsciously "started a bar tab" and are beginning to add up examples of the other person not meeting your expectations. This "tab" may negatively influence your behavior, as the weight of previous unaddressed issues can cause you to overreact to an issue in the future.

So, what can you do? (Re)set expectations give corrective feedback

The good news is that even if you didn't address it in the moment, you have the power to course-correct and go on to have a positive productive relationship with your mentee/supervisee.

You just need to revisit supervisory task #1, (re)setting expectations and #3, giving kudos and corrective feedback, and you may need some closer coaching for a little while from the Inclusive Mentor Fellows (IMF) team to get your professional relationship back on track.

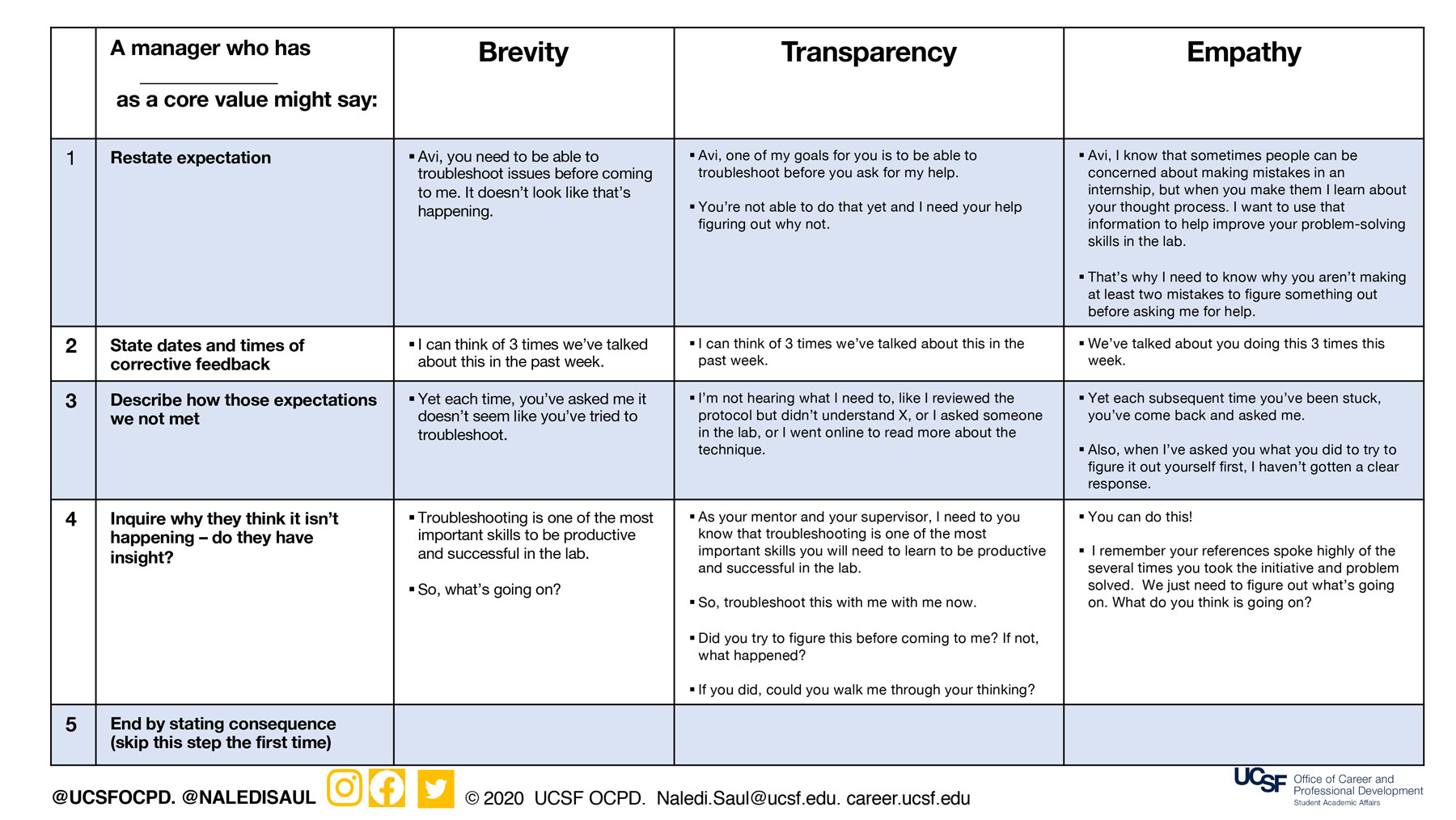

A reminder about feedback: it will help you if you use language and ground yourself by engaging from a place of a core value for you. As you can see from the example, while the 5 components of giving corrective feedback are the same (view sample corrective language PDF by clicking here), a managing mentor who values brevity might approach this conversation a little differently than someone who has other core values, such as transparency or empathy. Can't read the slide? Review the text below:

A managing mentor who has Brevity as a core value might say:

A managing mentor who has Transparency as a core value might say:

A managing mentor who has Empathy as a core value might say:

How do you handle the situation if you already "under-responded" earlier?

You might be tempted to "let it go" for now and prepare yourself for the next conversation - because there will probably be a next time. But another reasonable strategy is to briefly revisit the situation. There are three main touchpoints in this conversation:

"Jane, I've been thinking about it, and realize I need to revisit an expectation that I have for you. I know we touched on it briefly, but as your mentor/supervisor, it's only fair that I am clear about my expectations so you can meet them."

- Sample opening language when you need go back and more clearly (re)set an expectation and give corrective feedback that you under-responded to in the moment.

- Let them know how your thinking as progressed: "Jane, I've been thinking about it, and realize I need to revisit an expectation that I have for you. I know we touched on it briefly, but as your mentor/supervisor, it's only fair that I am clear about my expectations so you can meet them. Even if you let me know that you were going to be late for a meeting, if you are more than 15 minutes late, I need you to contact me again with a new estimated time of your arrival. That way I can figure out how to use my time most effectively. Does that make sense? Do you have any questions?" Know that the person may - for example, the person may be in the tunnel on BART and their phone may not work, or Muni is delayed, and there is no information on when they will be up and running again. It's important for you to hear any concerns on the part of the other person about meeting your goals and talk with them about how you expect them to address them.

- Confirm your workstyle: "Jane, I am a bit of an internal processor/I tend to be very cautious about giving corrective feedback until I am sure I understand the situation, so it may be the case that I give you corrective and kudos feedback a little later, rather than at the moment. Please know that I will make every effort to share expectation feedback in a timely manner, because it's important to me that you have a mentor/supervisor that is transparent about what you need to do to succeed, rather than try to guess."

- Reconfirm your intentions/commitment to their success. "Please know that (as I said during our interview) my goal when giving corrective feedback is not to embarrass or nitpick - it's to set clear expectations and support you in achieving both your and my stated goals."

If you meet with your person regularly, you can create an ongoing agenda item titled "Feedback" so you have a regularly designated space to discuss issues. You can also hold off on discussing the situation. But the second time the person commits the same error, address it and acknowledge that it would have been better if you have more thoroughly addressed the situation earlier - so you signal to the person that you are "tracking" this issue, and that it is important to you.

Addressing a blip can be the first time your professional supervisory skills are being tested. People sometimes need support or to practice the language involved in having this conversation. Remember check-in with us for coaching and support!

-Written by Naledi Saul, Karen Leung, James Lewis and Laurence Clement (UCSF OCPD and CCSF Biotechnology Program), supported by an NSF ATE grant.